The Good Ol’ Days of QBasic Nibbles

Let’s talk about an ancient programming language! I think we can all learn things from history, and it gives us grounding to realize that our time is just one time among many, to see what people in the past did differently, what they got wrong that we would never do now, and also to see what they got right.

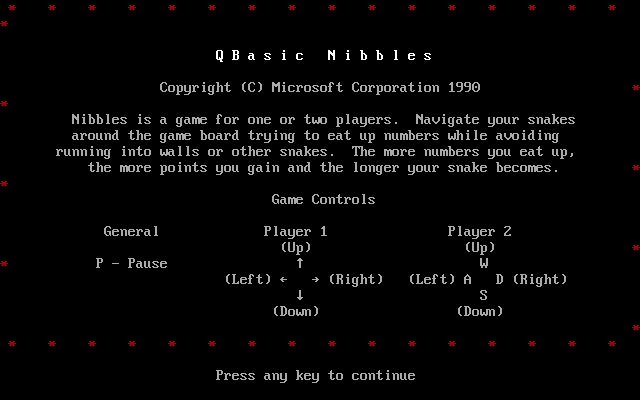

Do you remember MS-DOS? Do you remember that it came with an interpreted programming language? From MS-DOS 5 onwards, it came with not Python, not Javascript or R or Matlab, but a dialect of BASIC. But I think most people, especially most people my age who were children at the height of the MS-DOS era, remember it for the games, the two sample programs that came with it, namely Gorillas and Nibbles (their name for Snake).

Nibbles is extra near and dear to my heart because not only is it the game that I better enjoyed, but more interestingly because it’s the first “large program” that I ever did work on (for me as a child, “large” meant multiple subroutines), and the first existing program I ever modified.

So recently, I tried to see if I could find it. And indeed, I could.

I just needed DosBox, the QBasic

interpreter (you want

QBasic EN 1.1), to run it. After that, you just need the program

itself, after which, you can throw them in a directory, “mount” it from

inside DosBox, and run QBASIC.EXE and use its very discoverable

interface (by 90’s standards).

It looks a little less impressive in such a small little emulation window, but of course at the time it took the entire screen of an entire CRT monitor, and was the best technology available for me to interact with.

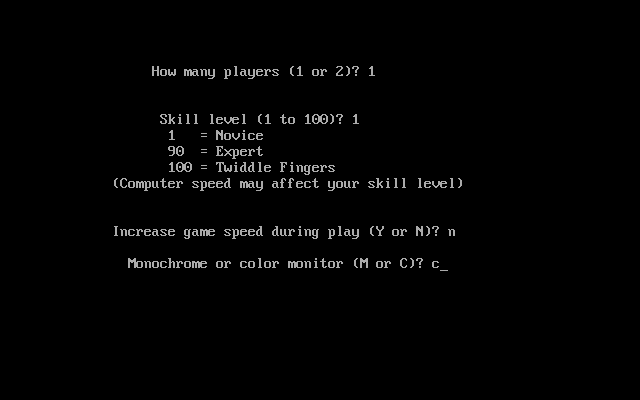

Nibbles was a sample game designed for you to learn to program as well as having fun with. True to its time, it had a little set-up interface where you answered questions in a very basic prompt-and-respond TUI before you could start playing:

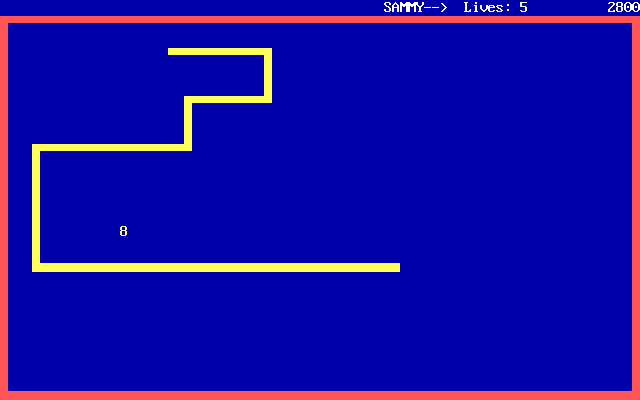

You ate numbers going from 1-9, which were easy to display – the program, though a video game, runs in text mode! – but at the time I just appreciated that it helped you keep track of how far along in the level you were. So I decided to take a look at the code and discuss it a little bit.

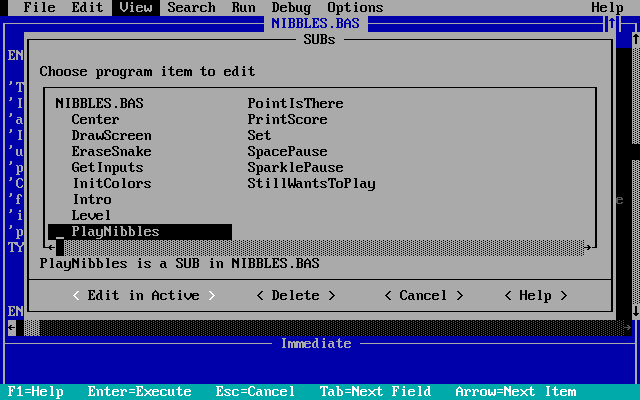

The first thing that struck me was how short it was – at 721 lines, this is a rather short source file, a “simple” module or class, let alone a whole program! I suppose things do seem bigger when you’re a kid.

But also, I didn’t view it as one block of size-12 text on a high-resolution monitor. I read it in QBasic’s built-in code browser where it showed up as 14 different logically separate parts, at the time an overwhelming number:

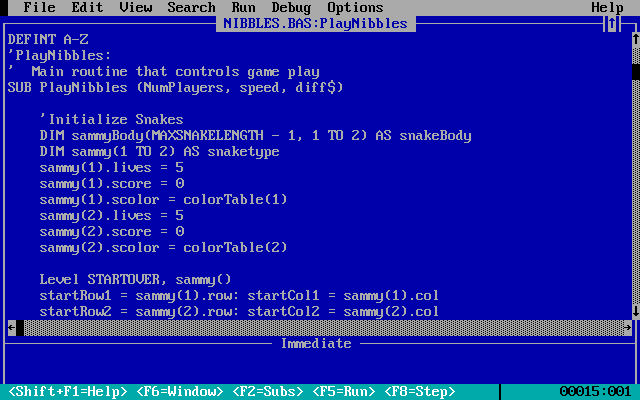

And this is then what the subroutine would look like:

Code browsers are great, and this interface is a solid reminder that

subroutines are a very early form of modules, especially given that

in QBasic, these subroutines could contain their own

sub-subroutines

using the more traditional

GOSUB command.

So let’s talk about this programming language and program that once people used to get real work (and real play) done.

First off, we see some mutable global variables, a big no-no by modern standards, but can you really blame them when their scope is no larger than that of a small modern class, where the fields would be effectively global within the context of an instance?

But also, to my pleasant surprise, there were also some global

constants,

and they are marked as such, with

the CONST keyword. In fact, as we see in

multiple

places,

QBasic is actually strongly typed, sometimes even using

the

sigils,

for which the BASIC family is infamous.

The “B” in BASIC stands for “beginner,” and that is exactly the target audience QBasic was designed for. So it’s really refreshing that in the past they didn’t have this notion that types were too advanced for novices, or perhaps too tedious, that an easy-to-learn programming language wouldn’t have you declare them.

Or, of course, maybe duck-typing was seen as too difficult or inefficient to implement. But in that case, why did they have what I imagine would be an equally difficult compromise measure, alphabetically-based type defaulting.

To be fair, for a long time I had no idea what DEFINT even

meant, but DEFINT A-Z certainly seemed like an appropriately mysterious

and even badass way to start a subroutine, a magical invocation, covering

the ends of the alphabet to start off each page of code.

Obviously, QBasic is not object oriented. Its fundamental notion of module isn’t a class, but rather a subroutine or function. These two notions were distinct: functions returned values (like in math) – though they could also have side effects – and subroutines did not. (Both had strongly-typed arguments, however).

This might seem an odd distinction to make, but it makes sense at a certain level. Especially syntactically, subroutine calls definitionally must be the top-level construct of a statement. And lo and behold! – they do not require parentheses around their arguments whereas functions do.

There’s really no reason not to do something like that in Rust, come to think of it. And come to think of it, Haskell makes a vaguely similar distinction, where if what others would call a “function” does IO and does not take arguments, it’s not a function at all, but a special value known as an “action,” which can then only be called in certain contexts.

So what did I do with this? I added more action keys. I added keys to speed up and slow down gameplay on command, so that if you pressed the arrow in the direction the snake was currently going, instead of doing nothing, it sped up the snake. Pressing the opposite direction of where you were going would then slow it down. And then, I wrote new levels, using the existing levels code as a baseline.

And then, after that, I began to attack the

main subroutine’s main loop. I thought it would be cool

if multiple numbers could be on the screen at the same time,

but this required modifying how the location of the numbers were

stored, replacing the

two

variables

indicating their current location with a two-dimensional array of boolean

values (represented by 0 and -1 – integer/boolean distinctions were

not yet well-established).

I wish I still had the code. But more importantly, I’m grateful that the Microsoft of the ’90s, as evil and monopolistic as it was, saw the need to put a programming language, a little IDE, and some sample programs and include them with their operating system. Bill Gates was my hero when I was a small child – before I knew what anti-trust was – and the fact that Microsoft made sure that computers came with plenty of fun corridors for me to explore was a huge part of why.

But also, there was no particular reason why the stuff I was doing couldn’t be done by any other elementary schooler, if there were interest in the schools in teaching it. Variables in programming are far more concrete in their meaning than variables in algebra – for one thing, their values actually vary with time, which made me think the variables in algebra were a bit of a misnomer.

And yet, programming isn’t even a required course in most American high schools. And that, I think, is a real shame. I understand that most schools don’t have the resources to do a good job of it, and that also, honestly, is a real shame.

Subscribe

Find out via e-mail when I make new posts! You can also use RSS (RSS for technical posts only) to subscribe!

Comments

If you want to send me something privately and anonymously, you can use my admonymous to admonish (or praise) me anonymously.

comments powered by Disqus