Operating Systems Part II: Modern Operating Systems

We use operating systems all the time in our life, whether designed for a computer, a phone, or for a server we’re more indirectly interacting with, but a lot of people don’t know very much about what connects the different systems we use, and what makes them distinct. We discussed fundamental concepts of operating systems in the last post, so in this post we will discuss how some of the same concepts apply to modern operating systems, going over them one at a time.

macOS#

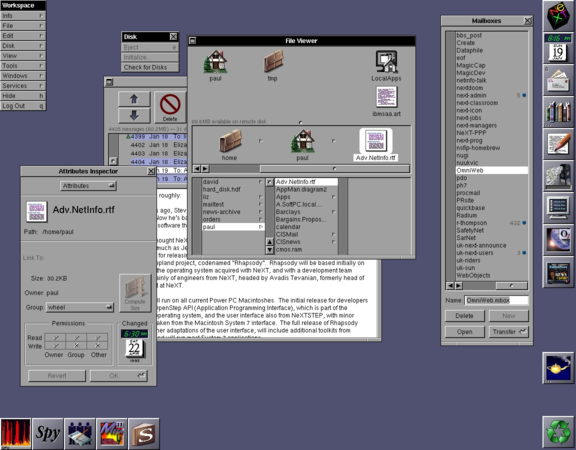

Unix moved on from controlling dumb terminals to having several graphical user interfaces. When Steve Jobs was fired from Apple in 1985, he started a company called NeXT to develop NextSTEP, a version of Unix with graphical user interface ideas, some from his work with the Macintosh, some developed independently:

When Apple was struggling to bring its operating system into the modern era, when Mac OS System 9 was still using cooperative multitasking, Apple bought NeXT and brought Steve Jobs back into leadership to turn NextSTEP into the next version of Mac OS, then called Mac OS X for the Roman numeral 10. In spite of superficial similarities to previous versions – the NeXT interface was changed to look more like previous Mac OS systems – and application compatibility (which was bolted on by running Mac OS System 9 as a single process within Mac OS X, which shows how much more sophisticated Mac OS X really was), the new version was completely different software descended from the original AT&T Unix.

It used to be common wisdom in some IT-savvy crowds (including a Best Buy salesman in my hometown when Mac OS X first came out) to claim that Mac OS X was a version of Linux, but this is not true. Linux is one of many operating systems that come from the Unix tradition, and Mac OS is a different one, sharing much of the Unix core instead with FreeBSD, a much less common version of Unix descended from the version developed at UC Berkeley (BSD stands for Berkeley Software Distribution).

For “desktop” computers, including laptops, macOS is now by far the most installed brand-name Unix operating system, and even if you include Linux in a broader category of Unix-like operating systems, it still is the most popular one on the desktop.

This is in spite of the fact – or perhaps because of the fact – that macOS doesn’t really emphasize its Unix “underpinnings.” Its graphical user interface is proprietary to Apple, and there’s often macOS-specific libraries that circumvent or supercede equivalent Unix ones, especially when focusing on the GUI applications.

They also don’t invest a lot of resources into making their command line interface friendly or powerful. Most Unixes make it easier to install new applications and frameworks via command line, and the command line is not particularly well-integrated with their graphical interface, to the point where it sometimes seems like their GUI is next to Unix rather than being built on Unix.

Finally, strangely for a Unix, Apple does not provide a server version of its operating system, making it difficult for software developers for Macs to be able to run server-side tasks like bulk automated testing on the same environment as their workstation.

iOS, watchOS, etc.#

iOS, watchOS, and their ilk are locked-down versions of macOS. Unlike on macOS, each application is locked into its own directory and can only access its own files, rather than being able to access any files owned by the current user. The security features of Unix are applied to isolate applications from each other rather than users, and the user doesn’t really see the concept of the file system — instead, each app simply remembers information for the user, and presents how its organized in its own way.

Since only one application is visible at a time on many of these devices, this gives it a feel similar to an old single-tasking operating system, where each application is more its own universe. Since they don’t visibly share a file system, the applications also interact less with each other.

The most scary thing about these operating systems is that they’re set up to protect the owner of the device “from themselves.” Only Apple-approved applications can be installed unless you jailbreak the device, which voids the warranty. Apple constantly lobbies for jailbreaking to be made illegal, they claim for the users’ protection and to prevent users from illegally copying apps, but also because they get a huge cut of all sales done through iOS apps, which Spotify claims is against European law.

Open Source and Linux on the Desktop#

The open source movement, and its more opinionated cousin the free software movement, believe, to various extents, that it is valuable for software to be open source (or alternatively phrased free as in speech). This means that anyone can read the source code to the software, the version of it that is human readable and editable by actual programmers. It also means that anyone can make modified versions of it, and publish them, usually with different branding. Some open source/free software licenses require those modified versions to also be open source, while others allow them to be proprietary, but in all cases, the fundamental nature of open source software is that anyone can make their own version (given sufficient programmers and time).

Linux (sometimes called GNU/Linux because Linux technically only refers to one part of the operating system, the kernel) is an open source reimplementation of Unix. It organizes software in the same way that Unix traditionally would, is written so that Unix programs can treat it as yet another version of Unix (of which there were already many incompatible versions), and follows the design of Unix function call by function call, command by command.

Linux is a really big deal on the server, and as a component of the Android operating system, as we’ll discuss later. It also is usable as a desktop operating system in its own right. It inherited a graphical user interface framework from Unix, known as the X Windowing System or X Windows, and the open source movement inspired a lot of work writing desktop environments within that framework, so that there could be an entire modern desktop operating system that was open source.

Throughout the 90’s and 2000’s, many Linux enthusiasts would hope that someday, a completely open source operating system could reach common use. Articles would be written claiming this was immanent, to the point where it became an easy-to-mock cliche: “This is the year of Linux on the desktop!”

Ultimately, though many companies tried, no one succeeded in arranging for it to be pre-installed on mainstream desktops or laptops nor in polishing it enough to convince the normal user to install it over what their computer came with. It is now a mostly-usable operating system, should you choose to install it on your computer or buy a computer wiht it pre-installed (which is an option some manufacturers now market towards software developers). It is very well-suited for programming for reasons we’ll discuss later, but still a bit awkward for things like setting up Bluetooth or getting interesting features to work.

Windows NT, XP, etc.#

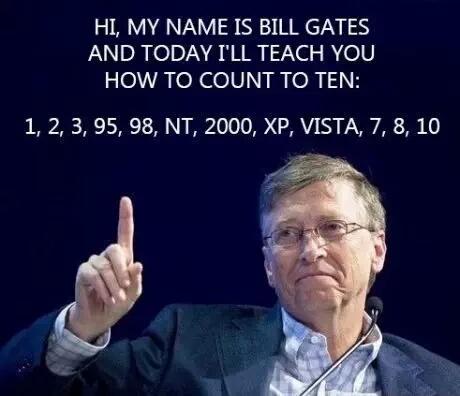

The history of Windows is intricate and arcane, and as a result, the Windows 10 of today has virtually no code in common with the Windows 3.1 discussed above. Similar to macOS, the Windows brand at some point was switched out with a better operating system implementation, although in Windows’s case, that implementation came from Microsoft’s “workstation” or “business” version, Windows NT.

Windows NT first came out shortly after Windows 3.1, and to avoid having a Windows NT 1.0, which might sound less sophisticated than the existing Windows 3.1, the very first version of Windows NT was called Windows NT 3.1. It was based off of OS/2, a failed collaboration between Microsoft and IBM to render MS-DOS obsolete, and it did not boot off of MS-DOS nor use MS-DOS as a layer.

Windows NT was designed from the beginning to support programs designed for other operating systems. For more sophisticated operating systems, programs have to go through the operating system to access hardware, by invoking procedures that invoke operating system code, and different operating systems provide different procedures. Based on what program you were running, Windows NT could support many sets of procedures (also known as APIs, but distinct from what API means on the web), which it called personalities.

Windows NT had from the get-go a personality to support Windows 3.1 versions, a 32-bit personality to support new Windows NT programs, and a personality to support MS-DOS (which involved much more machinery to give the program the illusion of more direct hardware access). It also originally came with personalities for Unix and OS/2, which eventually were removed.

As Windows NT supported traditional Windows programs as a personality, Windows and Windows NT co-existed for a long time. Windows 95, 98, and Millenium were versions of Windows that still used MS-DOS as part of their structure and which did not attempt strong security or rigor (though they did adopt preemptive multitasking), while Windows NT 4.0 and Windows 2000 (aka NT 5.0) were versions of Microsoft’s more sophisticated operating system, that could more or less run the same programs but focused on stability and workplace use (with the presumption of professional IT people), rather than Microsoft’s maniacal obsession with application support and its easy-to-use brand.

Eventually, in Windows XP, they made the switch. They risked worse compatibility with really old applications (after all, the operating system was completely switched out under the hood) in order to push everyone towards their more modern operating system. Windows XP was internally Windows NT 5.1 (and remember that Windows NT 3.1 was the first one because it borrowed its number from the other OS called Windows), and it replaced Windows 98 and Millenium as Microsoft’s flagship consumer OS.

Now, they don’t have to maintain two completely different operating systems anymore. Their server OSes are still distributed separately, but that is mostly for licensing and configuration reasons – it’s the same fundamental OS with different features enabled and different auxiliary programs shipped. All in all, Microsoft has a simpler tech architecture now that they’ve pushed everyone towards NT.

This is a good place to clear up a common misnomer: the Windows command

line, in modern NT-based Windows, is not a version of MS-DOS. It is only

related to MS-DOS aesthetically: It has a similar look to the prompt (C:\>,

C:\WINDOWS\>), and similar commands to do similar things (dir to list files

instead of Unix’s ls). It is simply the Windows command line.

Furthermore, support for MS-DOS binary compatibility was finally dropped with the transition to 64-bit computing, not because Microsoft wanted to, but because that would require a processor mode that AMD (and therefore Intel) decided not to support in their hardware.

You can’t, on the AMD64/Intel64 platform, have a 64-bit operating system and a “virtual 8086” mode process, where the processor would have to pretend to give you full control over the computer and pretends to be an ancient MS-DOS-era computer while also giving final say to the real 64-bit operating system. Intel32 supported this for 32-bit OSes and 16-bit MS-DOS compatibility, but I suppose the processor manufacturers thought the 64-bit vs 16-bit compatibility bridge was just a bit too far.

Microsoft Windows’s Monopolistic Market Dominance and the Open Source Movement#

In the 90’s and 2000’s, Microsoft had a lot of power through Windows. It constituted a monopoly on consumer operating systems, and people were scared to run other operating systems, because application compatibility was a big deal. Only major application vendors had the resources to support two operating systems (which was much harder in those days), and so having a different operating system (especially an ill-supported open source operating system like Linux) could cut you off from the rest of the computing world.

Microsoft used this power to control the application market, because any application it bundled with the operating system would drive any competitor out of business. It did this any time it thought an application was interesting, including writing its own web browser that drove Netscape out of business, finally attracting a lawsuit that almost split Microsoft into multiple companies. When that didn’t happen, it looked bad for the computer industry.

Microsoft also had corrupt relationships with computer manufacturers. Deals were signed where the hardware vendors would have to exclusively install Microsoft Windows on their computers, or else pay Microsoft based on how many total computers they sold rather than how many came with Windows. This meant that Microsoft didn’t actually have to improve Windows to compete; they could just rest on their laurels due to their shrewd and blatently illegal business dealings.

At that time, it seemed like the only way to break Microsoft’s competitive hold was compatible, open source alternative versions of everything. OpenOffice was written to try to be an alternative to Microsoft Office, but it was a non-starter unless it could read and write Microsoft’s proprietary Office file formats. Similarly, Mozilla Firefox, the first web browser to erode Internet Explorer’s hold on the web, only worked on many sites because it used to be configured by default to tell web servers that it was Internet Explorer rather than identifying itself honestly.

The crown jewel of this effort would have been working compatibility with Windows programs on another operating system — at the time, that was often seen as the only hope for breaking Microsoft’s monopoly on operating systems. Two efforts co-existed in that regard, Wine and ReactOS.

Wine was the more serious effort, which would have allowed Windows programs to run unmodified on Linux, including Microsoft Office, which was the only program that could perfectly read Microsoft Office documents. Wine would provide Windows applications with a personality, like Windows NT had, where they could call Windows’s library functions, and have them translated into the equivalent series of Linux library function calls to get their work done.

ReactOS was fascinating to me at the time because it attempted a complete open source reimplementation of Windows NT. Programs running on ReactOS would act like programs running on Windows because the operating system was designed from the beginning to act like Windows.

Neither of these projects gained enough stability to be used in any production setting. What ultimately lessened Microsoft’s stranglehold on power was the fact that nowadays, it’s not really relevant for most applications what operating system you use, because applications have transitioned to the web for deployment.

Nowadays, when you want to do something new with your desktop or laptop computer, you don’t install a new application (although interestingly, you still do with your phone). Instead, for the most part, you go to a website, whether for matchmaking services, communicating with people through many different means of communication, or ordering food to your apartment. The local program you buy at a store, or even download over the Internet, has been obsoleted by just going to a website, where you don’t even need to install anything. And as a result, Microsoft’s biggest stranglehold was eroded from a direction they barely expected.

They tried to hold on, as long as they could, by making their web browser, Internet Explorer the standard web browser, and encouraging websites to use Internet Explorer specific features. Eventually, Firefox was compatible enough with Internet Explorer to break through that monopoly and force Microsoft to update its browser, which led to the current situation — where Chrome is becoming the new monopolistic web browser and now it is Google that is close to single-handedly controlling our primary platform for deploying applications.

Linux and Unix on the Server#

I mentioned before that Linux and macOS were both popular among developers. Linux certainly allows a lot of customization, and you could see how that would be appealing for advanced users like many developers are – but that doesn’t really explain the popularity of macOS, which is the opposite.

Really, Linux and macOS are popular among developers because they are Unixes. Unix — and Linux, which is now basically the best Unix for most tasks — never waned in popularity in the minicomputer space, which evolved into the server space. When you are running a server, having a powerful (and programmable) command line is a huge plus, and not having a smooth GUI experience or drivers for every consumer device is a non-issue. Linux is the de facto standard for server operating systems now, and when developing applications to run on the server (like the server side components of any web application, including Facebook, Twitter, GMail, and more or less any you can think of), it is useful to have a match between what you run on the server and what you run on your personal computer.

macOS provides a close enough match to Linux servers to be useful for development. Most Linux software also runs on macOS, because of their shared Unix heritage and continuing efforts to keep compatibility. The compatibility isn’t perfect, and many programmers like the flexibility that comes with Linux (and don’t mind the inconvenience), and so Linux is also popular among developers as a client OS.

Windows is actually actively trying to catch up with macOS in this domain; it has introduced the Windows Subsystem for Linux, an NT-based personality that allows Windows to run Linux programs, unmodified. This is an impressive technology marketed at devleopers and used for practical applications by many people I know.

What is a server?#

What does a server do? It waits for incoming connections from other servers and from client computers like your laptop or phone, and responds to requests. It stores your data in databases and file systems, and does the heavy lifting that needs to be done by a more powerful computer than you really need to have in your own home. We interact with servers every time we use a web browser or an e-mail client, and most phone apps and games have a server-side component — certainly if they involve coordination with other people and other phones!

As the “cloud” grows as a concept, more and more of our computing is done on servers owned by big companies. We store our documents and spreadsheets on Google Drive, keep our contact information on iCloud, or let our photos be saved on Instagram. All of these services use Linux to power the servers that actually store the data and provide it to us in an organized and secure way.

Android#

As mentioned earlier, Linux is technically only one component of the operating system called Linux (or rather the family of operating systems, because many companies and organizations leverage its open source nature and distribute their own Linux-based operating systems, and there is no one official complete distribution), namely, the kernel. The kernel is the portion of the operating system that runs in a privileged mode on the processor, which forces the applications to go through it rather than access the hardware directly (as on MS-DOS).

Android uses the Linux kernel — but nothing else from the operating system commonly called Linux. Like iOS, it uses its kernel in an idiosyncratic, locked-down way — not quite as locked-down as iOS, but much more locked down nevertheless than any desktop operating system.

Android is open source, but you need to pay Google to use their app store and standard apps and brand. Off-brand Android can only be used in practice by companies rich and powerful enough to build out their own app store, like Amazon. Being able to run Android apps would be a relatively easy way for another mobile OS to gain a pre-existing developer base.

ChromeOS#

And Google somehow, after writing Android, wanted yet another Linux-based operating system. ChromeOS, popular in American public schools like Mac OS was in my school days, is exactly what it sounds like: a laptop operating system where you just run Google Chrome. With so many apps in the browser anyway, what’s the downside?

In a ChromeOS context, from a user’s point of view, you begin to wonder what the difference is between a browser and an operating system, really. An operating system lets you run multiple applications — but now those are just different browser tabs. Who cares whether the Linux kernel or Chrome itself are the pieces of software that separate the applications from each other — from the user’s perspective, it’s all the same.

If you unlock the developer mode, you get a somewhat dumb version of “Linux on the desktop,” with a Linux command line interface. This is convenient for people who only want to use the web and log into remote servers, which is a surprisingly large demographic.

Subscribe

Find out via e-mail when I make new posts! You can also use RSS (RSS for technical posts only) to subscribe!

Comments

If you want to send me something privately and anonymously, you can use my admonymous to admonish (or praise) me anonymously.

comments powered by Disqus